Beyond Leveled Reading: How to Give Struggling Older Readers the Right Kind of Challenge

After reading

"Why one reading expert

says ‘just-right’ books are all wrong", I suspect that Shanahan and I agree more than we disagree. However, I worry that - especially because many people don’t read beyond headlines - an important point may be obscured.

By Margaret Troyer, Ph.D.

Director of Literacy Research & Development

SERP Institute

After reading "Why one reading expert says ‘just-right’ books are all wrong", I suspect that Shanahan and I agree more than we disagree. However, I worry that - especially because many people don’t read beyond headlines - an important point may be obscured.

First, the article notes that Shanahan is opposed to leveled reading “mainly from second grade onward.” Prior to second grade, when students are focused mainly on building phonics and decoding skills, differentiated small group instruction is appropriate so that each group may receive explicit instruction and practice with the phonics skills they are currently working on (NRP, 2000; Connor et al., 2013).

The article goes on to acknowledge that grade-level texts are not appropriate for students who read significantly below grade level. Shanahan says, “If a fifth grader still can’t read, I wouldn’t make that child read a fifth-grade text.”

Given my background and work with the

Strategic Adolescent Reading Intervention (STARI), I am far more concerned about the fifth grader - and the sixth grader, and the high schooler - who cannot yet read on grade level, and the impact articles like this one may have on this group of students. Typically, these students have spent years holding grade-level texts in their hands that they cannot decode or comprehend. These students need something different.

Shanahan uses the analogy of a mother teaching a child to tie their shoes. As the mother of an 8-year-old who still can’t tie his own shoes, this analogy resonated deeply. And

I know what I’m supposed to do. Some days, there is time for him to mess around trying to tie his own shoes, while I stand off to the side patiently coaching. More often, though, we simply need to get our shoes on our feet and get out the door. And on those days, we use Velcro, or I tie his shoes for him. This more accurately represents the situation that most secondary teachers find themselves in. Secondary social studies, science, and even ELA teachers are responsible for covering content. When assigned texts far outstrip students’ current comprehension skills, that’s what leads to “Velcro solutions,” like teachers reading aloud or summarizing the texts for students - neither of which builds students’ reading skills. (And some days, my 8-year-old is frustrated because he can’t do something he knows he’s supposed to be able to do, and he doesn’t want to hear my coaching. This is a real issue for older struggling readers as well.)

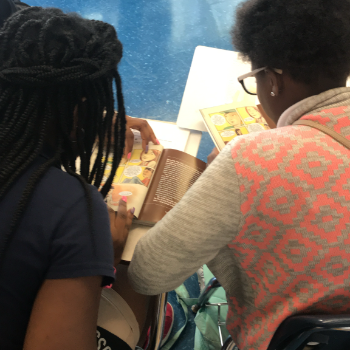

Yes, students who read below grade level need teachers to guide them to understand complex and challenging texts - but they need texts that are at an appropriate level of challenge for them. To be clear, we are not suggesting students be given books that are “easy enough that not much guidance is needed,” and we are not suggesting that students in a class read a dozen different texts so everyone can read at their “just right” level. Research suggests that comprehension instruction (unlike phonics instruction) is most effective with heterogeneous groups, where students can build off each other’s ideas and support one another’s understanding. In STARI, students read books with below-grade-level lexiles, but with characteristics of cognitive complexity, and the whole class reads and discusses one book.

I think Shanahan might agree with this. But I worry that the flashy headline suggests that all students should be reading grade level texts, no matter what. And given the fairly dire statistics on middle and high school reading skills, some of which are referenced in the article, there are compelling reasons to believe that this simply won’t work for most students.